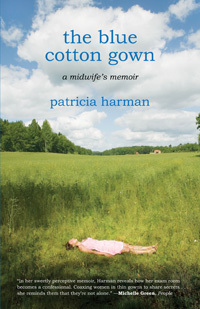

The Blue Cotton Gown: A Midwife's Memoir

Heather is pale and thin, seventeen and pregnant with twins when Patricia Harman begins to care for her. Over the course of the next five seasons Patsy will see Heather through the loss of both babies and their father. She will also care for her longtime patient Nila, pregnant for the eighth time and trying to make a new life without her abusive husband. And Patsy will try to find some comfort to offer Holly, whose teenage daughter struggles with bulimia. She will help Rebba learn to find pleasure in her body and help Kaz transition into a new body. She will do noisy battle with the IRS in the very few moments she has to spare, and wage her own private battle with uterine cancer.

Heather is pale and thin, seventeen and pregnant with twins when Patricia Harman begins to care for her. Over the course of the next five seasons Patsy will see Heather through the loss of both babies and their father. She will also care for her longtime patient Nila, pregnant for the eighth time and trying to make a new life without her abusive husband. And Patsy will try to find some comfort to offer Holly, whose teenage daughter struggles with bulimia. She will help Rebba learn to find pleasure in her body and help Kaz transition into a new body. She will do noisy battle with the IRS in the very few moments she has to spare, and wage her own private battle with uterine cancer.

Patricia Harman, a nurse-midwife, manages a women's health clinic with her husband, Tom, an ob-gyn, in West Virginia-a practice where patients open their hearts, where they find care and sometimes refuge. Patsy's memoir juxtaposes the tales of these women with her own story of keeping a small medical practice solvent and coping with personal challenges. Her patients range from Appalachian mothers who haven't had the opportunity to attend secondary school to Ph.D.'s on cell phones. They come to Patsy's small, windowless exam room and sit covered only by blue cotton gowns, and their infinitely varied stories are in equal parts heartbreaking and uplifting. The nurse-midwife tells of their lives over the course of a year and a quarter, a time when her outwardly successful practice is in deep financial trouble, when she is coping with malpractice threats, confronting her own serious medical problems, and fearing that her thirty-year marriage may be on the verge of collapse. In the words of Jacqueline Mitchard, this memoir, "utterly true and lyrical as any novel . . . should be a little classic."

An excerpt from The Blue Cotton Gown

Confessional

I have insomnia and I drink a little. I might as well tell you. In the middle of the night, I drink scotch when I can't sleep. Actually, I can't sleep most nights; actually, every night. Even before I stopped delivering babies, I wanted to write about the women. Now I have time.

It's 2:00 a.m., and I pull my white terry bathrobe closer, thinking about the patients whose stories I hear. There's something about the exam room that's like a confessional. It's not dim and secret the way I imagine a confessional is in a Catholic church, the way I've seen them in movies. I peer at the clock. It's now 2:06.

The exam room where these stories are shared is brightly illuminated with recessed lighting. The walls are painted off-white and have a wallpaper border of soft leaves and berries. There are framed photographs of babies and flowers and trees, pictures I took myself and hung to make the space seem less clinical, and a bulletin board with handouts on stress reduction, wellness, and calcium.

The room is not big. It's the usual size. If I had to guess, I'd say eight feet by ten feet. The countertop under the tall white cupboard is hunter green, and there's a small stainless-steel sink in the corner. Other than a guest chair, my rolling stool, and a small trash can with a lid, there's just the exam table, angled away from the wall, with a flowered pillow and rose vinyl upholstery. On it lies a folded white sheet and a blue cotton gown with two strings for a tie. The exam table dominates everything.

I don't drink for fun. I don't even like scotch. It's for the sleep. I can't work if I can't sleep. The scotch is my sleep medicine and I want it to taste like medicine. The little jam jar with the black line at three ounces sits in the bathroom cupboard. My husband fills it for me, then locks the bottle in the closet. I ask him to do that. When you have as many alcoholics in your family as I do, you don't take chances. On nights when I'm restless, I drink it down sip by sip, making a bad face after each swallow. Then in an hour, I go back to bed.

I stand now at the window listening to the song of the spring frogs and thinking of the stories the women tell me, and then, in the stillest part of the deep night, I sit down to write. I need to sleep but I need to tell the stories. The stories need to be told because they are from the hearts of women; the tender, angry hearts; the broken, beautiful hearts of women.

Heather

It's Monday morning and I'm late again. Waving to the receptionists, I rush through the waiting room. They turn to greet me in their aqua checked scrubs but keep on with their work. I know they keep track of how often I'm tardy.

"Hi, Donna," I say as I pull open the heavy cherry door to the clinical area. Donna, at the checkout desk, looks over her sleek hornrim glasses and gives me a smile. The phone is tucked under her ear and she's clacking away at her computer.

Around the corner and down the hall is my office. It's small, just enough room for a desk, a file cabinet, two bookcases, and a guest chair. The cream walls are lined with my photographs: the highland forest in full autumn color, a pregnant woman stepping out of the shower, and our barn with the red roof next to our cottage in Canada. On the window ledge are purple African violets rooted in a green pot that Tom threw on the wheel in his studio and a framed photo of the five of us last Christmas. I toss my briefcase into the corner.

In the picture, three mostly grown boys, Mica, Orion, and Zen, clown in front of the slightly crooked spruce tree. That's me in the back, with round pink cheeks, short straight brown hair streaked with gray, and wide blue eyes; a tall, girlish, middle-aged woman. Tom, stocky, slightly balding, with wire-rim glasses and short gray hair, stands with his arms around me. He's laughing too. It would take a miracle drug to get us all looking normal in front of a camera.

The Women's Health Clinic is located in Torrington, home of Torrington State University, on the fifth floor of the Family Health Center. Our private practice is composed of Tom Harman, ob-gyn; our two nurse-practitioners; and a staff of seven nurses and secretaries, all women. The suite, which we designed ourselves, is arranged in a rectangle with nine exam rooms, five offices, a lab, and a conference room. There's also a small kitchen, the waiting room, and the large secretaries' area up front. On two sides, windows run the length of the office. I wanted the staff and the patients to be able to look out at the sky.

Five minutes after I arrive, I'm standing in the exam room holding out my hand to a skinny young woman who stares at it as if she's just been offered something she'd rather not touch, a dead fish or rotten banana. She has short curly red hair, a beautiful girl, but she holds her head down like she doesn't know it. An eyebrow ring mars her perfect face. I pull my hand back and try again. "I'm PatsyHarman, nurse-midwife, you must be "-glancing at the new chart-"Heather Moffett."

Heather doesn't say hello or anything else. There's also an older woman and a young man in the room, so I start talking to them, turning first to the older lady who's sitting in the guest chair, clutch ing her large white pocketbook. "And you are family?" The grimfaced, gray-haired woman nods once. She inspects me through her glasses, clear plastic frames with rhinestones at the corners.

I was hoping she would introduce herself. "Heather's mother or aunt ?" I prompt. It's always better to flatter than insult, though the woman appears to be in her seventies.

"I'm her grandma."

This is not a cordial group, and I'm wondering what kind of conversation they were having before I came in. The air feels like cement just beginning to harden. "And you?" I turn to the young man.

"T.J.," he responds sullenly. That's all he says.

Heather is sitting hunched over on the small built-in bench in the dressing corner of the exam room, her arms tucked into her blue exam gown. T.J. swivels back and forth on my stool. The grandmother is perched on the one gray guest chair, so there's nowhere left for me to sit except the exam table, and that isn't going to happen.

"Before we get started, let's rearrange things," I say energetically. "Heather, you sit up here on the exam table. T.J., you sit where she was, and I'll take the stool." We all trade places and when the young man stands I realize he's over six feet tall. His hair reaches past his shoulders and he's good-looking, like a heavy-metal star in the eighties, thin and sensuous with flat gray-blue eyes. No one says anything. They just move to where I point.

"So." I start up once more. "It looks like you're going to have a baby, Heather. Were you trying, or did it just happen?" I ask it like this, not wanting to assume every teenage pregnancy is an accident. Heather shrugs and glances at T.J.

I try again. "So are you excited, or still in shock?"

"Excited, I guess," Heather says, not sounding like she is."Well, that's nice, then," I respond. The grandmother rolls her pale, watery blue eyes and crosses her ankles, which look purple and sore.

"Let me go over what you've written in your history, and then I'll ask you more questions. Today what we need to do is an exam and some lab work-" I don't get to finish.

"I got to puke," says Heather, standing up with her hand over her mouth and searching wildly around. The grandmother and I stand up too. The older woman opens her bag and comes up with some tissues. I take Heather's slender arm and lead her to the small stainless-steel sink. T.J. stays where he is. This doesn't involve him. Heather gags.

"Do you have time to get to the bathroom?" I ask. The patient stands still, her head down, her red hair hanging around her face. I pull the curls back, holding them out of the way. Nothing comes up.

"I'm okay I think," Heather whispers.

"Has she been vomiting a lot, Mrs. ?"

"It's Gresko, Mrs. Gresko. A fair 'mount, yes. Three, four times a day, seems like, maybe more."

I take the girl's pulse. It's rapid, and when I pinch the pale skin on her forearm, it tents, a sign of dehydration. "Are you keeping anything down?"

"Some," says the grandmother. "She's bleeding too." Our eyes meet, and when I look over, I see blood dripping down Heather's legs.

"When did this start?"

"Yesterday. That's why we called 'round for an appointment. I don't want nothin' to happen to this baby."

So much for taking a detailed, organized history. "You know, Heather, I've changed my mind. I'll read what you wrote on the OB form and ask you questions next visit. Since you're feeling so sick, I'd just like to get you a prescription for the vomiting and-"

"What about the blood?" T.J. challenges. "That isn't good, is it?"

"No, it isn't. It isn't a good sign, but it doesn't always mean something bad. How much blood is there?"

Heather looks at her grandmother.

"'Bout like her monthly," Mrs. Gresko says.

"Can you tell me when your last real period was?"

Heather shrugs.

"We can't be sure," says Grandma. "I tell her to write down her time but she don't."

Great, I think. "Well, why don't you lie back on the exam table and I'll feel your belly to see if I can get an idea." My hands palpate Heather's lower abdomen. There's a bulge halfway between her jeweled belly-button ring and the pubic bone, about right for fourteen weeks. Could the girl really be that far along?

"Give me a minute. I want to see if my husband, Dr. Harman, is available for an ultrasound." I leave, shaking my head, and trot down the hall. Looking through the window in the nurses' station, I see storm clouds have come in from the west.

Tom's two exam rooms are on the opposite side of the clinic, and both doors are closed, indicating there are patients inside. Behind one, I can hear voices, and I knock softly, nervous about interrupting him.

No one answers, and I tap again, louder, hoping he's not in the middle of a pelvic exam. Finally he opens the door. "What's up?" He's wearing a red checked shirt with a Beatles tie and black Dockers.His white lab coat is reserved for the hospital. He would wear jeans and a corduroy shirt to the office if I let him.

"I have a new OB that's spotting; can you do an ultrasound for viability and dating?" I ask. "Do you have time?"

Tom glances at his watch and shakes his head. "I have three patients to see before I go to the OR. Is she bleeding heavily? Can we do it tomorrow?"

I shrug. "It's not like she's hemorrhaging. But it's not good either, and they're anxious."

"Get her here in the morning, I'll squeeze her in." A middle-aged woman sitting on the exam table glares at me through aviator glasses. Tom closes the door, and I head down the hall, trying to decide what to say.

I could scan Heather myself, but even if I can find the heartbeat she'll need a second ultrasound to get an accurate gestational age. And if it is a miscarriage, I want Tom to be there to confirm it. The family won't like having to return, but tomorrow is best.

When I reenter the exam room I find the small group standing in a knot next to the sink. They quickly sit down. "She threw up," says Mrs. Gresko, as if it's my fault.

"What about the ultrasound?" demands T.J.

"I'm sorry," whispers the girl, looking down.

I go to the sink. They've cleaned it, but it still smells like vomit. The nurses will have to spray with disinfectant. "We'll have to do the ultrasound tomorrow. I'm sorry. If the bleeding gets worse tonight, come to the ER. I know you're worried, but you have to understand that if a miscarriage is going to happen, nothing can stop it. Just rest, get some ginger ale for hydration, and come in around ten. I'll write you a script for medicine that might help with the nausea, and you could try some peppermint tea. I have a feeling everything's going to be all right " I'm not sure why I say this.

Mrs. Gresko shifts in her seat and sighs with irritation. T.J. crosses his long legs in disgust. Heather studies her stubby blue fingernails.

So far she's uttered all of four sentences, and that's all I'm going to get.

A Reader's Guide for The Blue Cotton Gown

"In her sweetly perceptive memoir, [Harman] reveals how her exam room becomes a confessional. Coaxing women in thin gowns to share secrets ... she reminds them that they're not alone." Michelle Green, People

Questions for Discussion

- Nurse-midwife Patsy Harman reveals at the very beginning of her memoir that she drinks "a little." Do you think it's okay, either as a self-medicating procedure or as a coping mechanism, to drink the way Patsy does? Do you think Patsy's insomnia is a medical condition, or a result of her emotionally demanding profession? How do you deal with the stresses of your profession or everyday life?

- Have you ever known a teenager who was pregnant? Were you or anyone in your family ever in the position Heather Moffett, T.J., and Mrs. Gresko find themselves in (p.4)? In West Virginia, teen pregnancy is fairly common, and many of these young women carry their pregnancies to term (p.59). Are there different community standards prevailing in your area? Is a pregnant teen likely to have an abortion or perhaps place a newborn with an adoptive couple or agency?

- Do you feel there is a stigma associated with people who choose to place their babies for adoption in your community? Is it greater or lesser than that associated with abortion? Do you think it takes great courage to place a child for adoption, as Patsy says (p.60)?

- How do feel about Nila's willingness to have more babies despite the steadily increasing amount of danger to herself and the infant, and despite the fact that she already has seven children and is separated from her husband (p.10)? How do you feel at the end of Nila's story (p.269)?

- Throughout her memoir, Patsy references the obstacles facing families in Torrington, West Virginia; clinics like her own, who will take patients even without insurance and can no longer afford to deliver their babies because of the exorbitant cost of malpractice insurance; and patients who must apply for a medical card, but can easily not qualify if not "poor enough" (p.18), and are expected to pay $700 for a family healthcare policy on minimum wage. What do you envision as the ideal healthcare system?

- Patsy tells us she was taught not to mix religion with medicine, but she can't help but say a small prayer for some of her patients (p.21). What do you think about religion's place in healthcare? What about the issue of touch, as when Patsy hugs or otherwise makes physical contact with the women she is treatingis that acceptable? Do you think that any emotional investment in patients' lives has any positive or negative affect on their care (p.143)?

- Patsy chooses to help Kasmar transition, saying, "If the patient had been born with a deformity, some error of nature such as a cleft lip or a clubfoot, someone would help her. To Kasmar, her female body is just as much of a mistake" (p.93). She might have refused to help Kasmar based on her own beliefs. There are, of course, many differing ideas on what's ethical in regards to health. Practitioners can refuse to perform an abortion, even for an at-risk woman, and pharmacists can refuse to provide Plan B based on their religious beliefs. People in the military can refuse to participate in combat if they are conscientious objectors, based on religious, moral, or ethical grounds. Have you ever had to put aside your personal biases, reluctance, or questions to simply help someone else, or do what is right for them, or right in general? Do you think a personal moral code trumps a societal or even legal one?

- Patsy comments several times in the memoir about her patients' courage: Nila leaving the unhealthy relationship with her husband (p.13); the 20-year-old college student and her boyfriend placing their baby for adoption (p.59); Icy saying what she really believes (p.171); Marissa's optimism and humor despite all her health difficulties (p.214); Kasmar transitioning from a woman to a man in front of her colleagues, rather than simply leaving the state (p.220). What about her own courage and endurance? What do you think the book says about the human capacity to endure in general?

- The issue of sexual or physical violence against women first emerges in Nila's story. She leaves Gibby, but justifies not reporting him for giving her a black eye and continuing unwanted contact by saying, "We grew up together. You excuse a person you've known and loved this long. You understand them" (p.202). Then there is Penny, who was sexually assaulted by a gynecological resident when she was 17 (p.106). Patsy persists in trying to find the doctor, to stop him from assaulting again, up until the end of the memoir, but Penny quietly says, "I've forgiven the man. Maybe you haven't. It wasn't the worst thing to happen to me" (p.266). How are Nila and Penny both people of strength and weakness? Can you imagine letting a physical assault go unreported?

- There has been talk of placing a cap on malpractice lawsuits for many years, the argument being that lawsuits are driving up healthcare costs and driving doctors out of practice (p.110). Patsy and her husband have been forced to give up delivering babies because of the cost of their malpractice insurance. But there is also expert opinion that there are nearly 100,000 preventable medical errors in America per year. Do you think the peer-review committee that Tom discusses has the right to be tough on surgeons, or is the risk too high of driving apparently good doctors out, like Dr. Runnion? Have you also heard opinion that the medical insurance business is driving up premiums for increased profits, rather than out of actual need?

- Why do you think Patsy is so vigilant about her patients' health, but seems to neglect her own (p.168)? She even forgets to light the prayer candle right after she receives her own bad news (p.176), and later on she finds out that she has cancer (p.179). Is this common for people, do you think, to neglect themselves most? Is it more common for a man or a woman, or for someone in the medical profession?

- Patsy says, "I know that the removal of a woman's reproductive organs is the second most common surgery performed in the United States. Cesarean section is first. Each year, more than six hundred thousand are done. One in three women in the United States has had a hysterectomy by age sixty" (p.174). What do you think that says about the medical profession's approach to women's bodies, from minor cosmetic surgery to major invasive surgery?

- Tom seems not to see Patsy's hysterectomy as a crisis (p.174-175). Do you think Tom's attitude, especially as a male doctor, is reflected in the medical community at large and contributes to the high rate of hysterectomies? There also seems to be a lack of concern about the sexual pleasure of women; Tom is sure it'll be fine, Patsy knows it might not be. Is this cavalier attitude another reflection of a popular sentiment towards female sexuality in society? Compare Rebba's case (p.27) and Patsy's.

- Patsy says, "I'd feared the hysterectomy more for the loss of my sexuality than for potential complications" (p.185). When a woman loses a part of what she feels makes her a woman, Patsy's sentiment is not uncommon (for mastectomy patients, for example, as well as cancer patients with hair loss), but what do you think it says about women, people in general, and/or society linking their identity with their bodies? Or more specifically, what is traditionally considered to make a woman female? What does this say about gender identity? (Kasmar p.193)

- Kasmar's partner Jerry is having a difficult time adjusting to Kasmar becoming a man (p.194). Marissa's husband can't deal with the major change in her health and leaves her, telling her "he hadn't signed up to marry an invalid" (p.212). Is it okay to leave a relationship when your partner makes or experiences changes that you feel makes you incompatible?

- Patsy says she tells her story about running away from home to her patients dealing with serious personal problems "because there was a time when I told no one" (p.127). Holly never told anyone about her daughter Nora until she met Patsy (p.19). Shiana couldn't talk to her parents or her fellow sorority sisters (p.35). But people need to talk about their traumas. Even Pappy at the trailer park scene of Aran's death, Patsy realizes "has been through a traumatic event too and needs to talk about it" (p.241). Do you think many more women keep all their problems to themselves and let them fester, possibly to the point that Patsy did? To the point that Aran did? What's the significance of people's general impulse to share their stories in life?

- How do you interpret Patsy's dream? She says in her dream, "I too am naked under my exam gown

I pray, adoring these women whose lives are as knotted and scarred as my own

Like a red hawk, I rise

the four women are flying with me" (p.113)?

Did You Know

?

- The American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM) estimates that soon one in ten babies in the U.S. will be delivered by certified nurse-midwives. Ten years ago, only 3 percent of births in the US were attended by nurse-midwives. Worldwide, midwives deliver more than two-thirds of births.

- In the U.S., endometrial cancer is the most common cancer of the female reproductive organs and the fourth most common cancer for women. There are a little over forty thousand cases each year.

- Each year, women experience about 4.8 million intimate partner related physical assaults and rapes. Nearly 7.8 million women have been raped by an intimate partner at some point in their lives.

- According to the U.S. Census Bureau, nearly 46 million Americans under the age of sixty-five were without health insurance in 2007, their latest data available.